A new Methodology to Assess Management Tools

Peter Prevos |

1052 words | 5 minutes

Share this content

The science of business, just like any other academic field of endeavour, seeks to understand the nature of reality. Scientists judge a theory not only on its ability to predict the future but also on whether it can be considered elegant. In the physical sciences, for example, Stephen Hawking admits that he longs for the day when nerds can wear t-shirts with a straightforward formula that explains everything in the universe.

The Science of Business

Business theorists are also drawn towards the aesthetics of their thoughts. The textbooks slaved over by MBA students all over the world are littered with two-dimensional matrices that purportedly explain everything from what business strategy to use or whether the divest whole business units. Famous examples are the BCG Matrix, Igor Ansoff's strategy matrix, the ubiquitous SWOT analysis, Porter's Generic Strategies and so on. Some more adventurous thinkers take it a step further and postulate slightly more complicated diagrams, such as the GE-McKinsey Matrix or Porter's Five Forces and of course his Diamond of national competitive advantage.

It is a comforting thought that the unpredictable nature of business reality can be expressed in simple two-dimensional diagrams that even the least intelligent manager can reproduce to impress his peers and superiors with.

Since I started my journey into business theory several years ago, it surprised me how much academic literature on business is separated from the popular books that managers read and apply in their daily work. A great moat surrounds the ivory tower of academic business schools. Most managers spend considerable time chewing the fat with academics when they attend university. But, as soon as they leave, there is little further interaction. The word academic is mostly used in a negative sense as an indication of something being of no practical use.

The Lucid Manager would not be a real business blog if we did not introduce our meta-matrix or ‘über-matrix' of the business sciences and management tools. So, let's take the blue pill and enter the world of the Management Theory Matrix, henceforth known as the LM (Lucid Manager) Matrix.

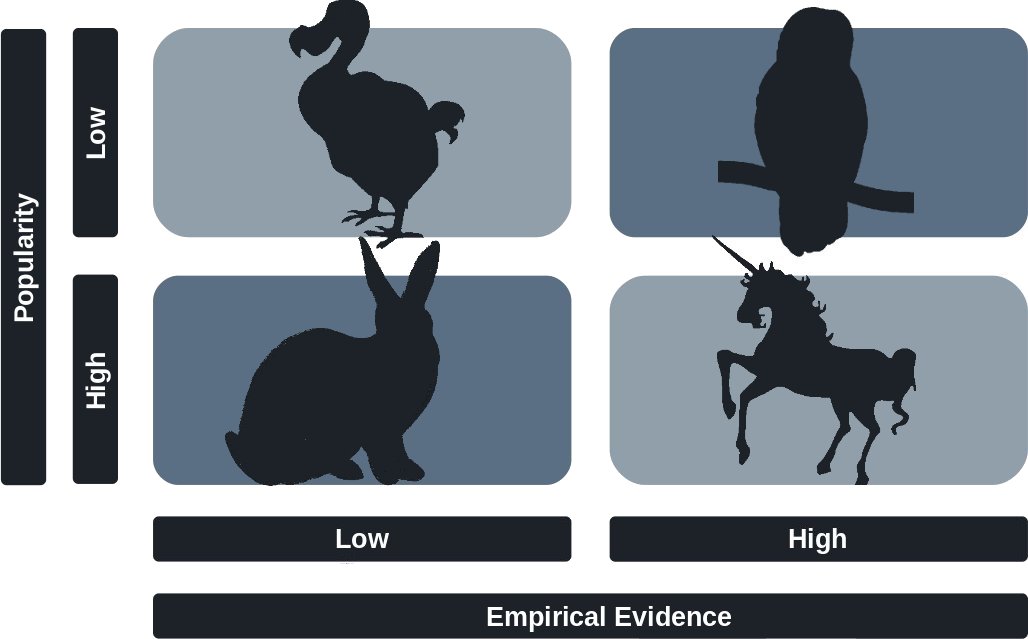

The first dimension of the LM Matrix is the extent to which theory is corroborated in reality. In other words, how much empirical evidence is available to support the theory. The second dimension to consider in the LM Matrix is the popularity of the theory. The popularity of a model can be easily tested by reviewing the best-sellers lists of internet bookshops and reviews in popular management magazines. To visualise the matrix and provide some metaphors, a zoological approach is used in the LM Matrix.

This method is inspired by the ubiquitous BCG Matrix and DiSC personality profiling. In the bestiary of business theories, we can distinguish four animal kingdoms, dodos, owls, rabbits and unicorns, each with their unique characteristics.

Management Tools Matrix

Dodos

When a management theory has a shallow empirical foundation and is neither very popular, it can be called a dodo. Just like the now extinct ugly flightless bird from the island nation of Mauritius was hunted to extinction by Dutch sailors in the seventeenth century, these theories are not able to withstand the evolutionary forces of social selection by managers and scholars.

Although the father of what we now call management science, Freddy Taylor, who himself was killing the dodos of his time, proclaimed to base his work on rigorous measurements of reality. More recent research of his private notes shows that this is more myth than reality. See Matthew Stewart's excellent book The Management Myth, which inspired to write this post. Taylorism and Scientific Management is thus an example of a dodo. Although it has spawned many modern theories, Taylor's original thought has fortunately perished.

Owls

Academic journals of management theory are brimming with valuable research, carefully undertaken and analysed using deep thought and sophisticated mathematical models. Prestigious journals rigorously select papers that can demonstrate a high level of empirical validation and predictive power.

The complexity of academic thinking is, however, not popular with managers. Most people in business are not comfortable with convoluted mathematics and abstract structures proposed by scholars. The ancient Greek goddess of wisdom Athena is often depicted with an owl perched on her head. These theories are as such called owls because of their great wisdom. Alas, owls are shy creatures that prefer the darkness of the night and are rarely seen in boardrooms and management workshops.

Bunnies

Most theories that win the popularity contest in the business ideas market dramatically lacking in empirical validation. Managers blindly accept Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs as a psychological truth and try to emulate the 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. They are called bunnies because they are cute and cuddly on the outside, but breed uncontrollably and can cause irreparable damage to the environment; burrowing holes and undermining the foundations of organisations.

Some authors, such as Jim Collins and his immensely popular book Good to Great, hide behind a veil of pseudoscience and undertake shallow research without the statistical rigour required in science. But his work is littered with tautologies and is lacking in critical analysis.

Unicorns

What would be expected the Cash Cow of management theory are those ideas that are corroborated with actual business practice and are indeed practised widely, are unfortunately as elusive as the mythical unicorn. But the unicorn stands for a hope of better times ahead.

Maybe one day a new age in business will e heralded, as was initially proclaimed by Taylor, and millions of workers around the world can sigh of relief when they are liberated from the dodos and owls, instead of riding unicorns towards the rainbow.

Epilogue

But what does this all mean you might ask yourself. The simple message that the LM Matrix proclaims is, in the words of Immanuel Kant: "Sapere Aude!", or in everyday language, dare to think.

A business theory is, in essence, social theory, and no aspect of reality is so difficult to capture in theory as the behaviour of human beings. Good business science is complicated and often requires deep thought and self-knowledge to be able to understand business. As a social science, a business can not be explained away in simple theories and matrices. Understanding comes with wisdom and insight that can just not be drawn in two-dimensional diagrams.

Share this content