The Value of Water — A Marketing Perspective on Tap Water

Peter Prevos |

2255 words | 11 minutes

Share this content

The value of water has been a topic of interest since the start of modern economic. Father of economics Adam Smith identified the so-called diamond-water paradox in The Wealth of Nations. The basic question he asked is what are useless diamonds so valuable, while the price of water is so low. This article discusses a model for the value of water and a method to describe the water value proposition.

The Value of Water in History

Thoughts about the value of water as as old as human culture itself. The Bible (Isaiah 55:1) sees water as a human right. A point of view that many people seem to have in debates about water prices:

Come, all you who are thirsty, come to the waters; and you who have no money, come, buy and eat! Come, buy wine and milk without money and without cost.

This invitation to the thirsty shows the importance of water in semi-arid cultures. This quote positions water as a human right to be shared by all without having to pay for it. Some have argued that water is a God-given right and should not have a price. The counter-argument is that the water might fall free from the sky, but the pumps and pipes needed to deliver it to customers is not.

Plato (Euthydemus 304B), refers to the Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes:

For only what is rare is valuable; and "water," which, as Pindar says, is the "best of all things," is also the cheapest.

Adam Smith, in his book Wealth of Nations (Book I: 4.13) described what has become known as the Diamond—Water Paradox.

Nothing is more useful than water: but it will purchase scarce any thing; scarce any thing can be had in exchange for it. A diamond, on the contrary, has scarce any value in use; but a very great quantity of other goods may frequently be had in exchange for it.

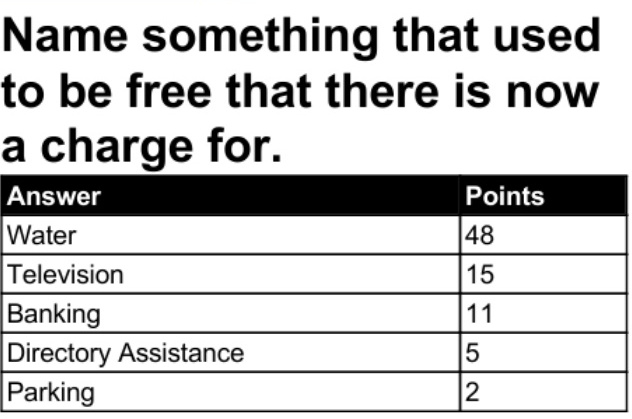

A more mundane example comes from the quiz show Family Feud. In an episode of the Australian version, they asked contestants what they though people answered when asked what should be free. Water was, perhaps unsurprisingly, the top answer.

The Value of Water

The value of water is not the same as the price of water. Price is an absolute concept, but value is an inherently subjective construct that only customers can define. It is often said that the customer is always right. Although customers might be wrong about facts, they are always right about how they feel about something. In order to use the concept of value in marketing we need to view it from the perspective of the customer, which relates to how they feel about the service. Following this line of reasoning, the definition of value is the difference between the perceived benefits and perceived cost. We should, however, not view benefits and cost only from a monetary perspective. The value of water is a multi-dimensional construct.

The Benefits of Water

The Hierarchy of Needs

Not all water use is, however, a matter of life and death. Customer use water for many purposes and in the case of reticulated water supply, they use the same water for drinking, hygiene, gardens, swimming and other recreational activities and as a transport medium for waste.

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs can be evoked to illustrate the multidimensional nature of the value of water. At the physiological level, we need water for hygiene and hydration. Water does, however, also fulfil social and psychological needs. A mundane activity such as gardening, which requires a lot of water, serves to meet the full spectrum of human needs, e.g. physical exercise, expressing creativity and creating a space to socialise.

Needs and Wants

To understand the value of water we need to define its benefits and distinguish between needs and wants for water. The marketing definition of needs and wants is very different from the common sense understanding of need as a necessity. Many publications on tap water distinguish between the water we need and the water we want, the so called discretionary use. This distinction is the a common-sense concept between needs and wants, whereby needs are of a higher order than wants. The common sense understanding of the difference between needs and wants is, however, incorrect as it denies the importance of higher order needs.

Needs

Maslow, as a humanist psychologist, believed that all human beings have a need for self-actualisation as much as they need food and water—the so called hierarchy of needs is not really a hierarchy. Physiological needs are just as important as the need for a sense of safety, a sense of belonging, self-esteem and self-actualisation. Therefore, the need for water includes uses other that hygiene and consumption. Recognising that sociological and psychological needs are just as important as physiological needs is paramount to be able to define the value proposition of water.

Evoking on Mallow's humanistic psychology, human beings need a lot more than just a minimal amount to survive. Human beings have sociological needs and psychological needs, and they all have to be met. They are all necessary to be a complete human being. To say that water used for gardening is not a need but "only a want" is wrong.

People need water to grow their gardens because they have a sociological need or psychological need. People have a garden because they want to invite friends and have a good time. Gardening also provides a sense of achievement, a significant psychological need. Needs are a mental state of felt deprivation. There is no threshold whether something does or does not classify as a need. Needs are psychologically innate within us. We cannot change of create these needs.

Wants

Hand in hand with psychological needs, customers have 'wants', which is the manner in which a need is satisfied. If somebody needs self-fulfilment, some people might do a PhD in marketing, other people might enjoy working in their garden, for which they need water. Everybody fulfils their psychological needs differently. The core task of a service provider is to understand these needs and wants and create a value proposition that matches customer expectations.

Marketing can not change or create needs, but it can influence what people want. Wants are culturally determined and can be shaped through communication, and education. The traditional Aussie backyard is disappearing because customer's values are changing. People are no longer interested in expressing themselves through their garden. The younger generation has experienced the prolonged drought and they have developed alternative ways to satisfy their needs.

The Cost of Water

The discourse about the price of water predominately discusses money. However, the cost of water is multi-dimensional. Besides money, people pay a psychological price a sociological price and a time price for water.

On the cost side of the value equation, dimensions other than financial cost, such as time cost should be taken into consideration. Additional to the money a customer pays for service, they also pay with their time. Using time to enjoy a service is an opportunity cost to the customer—any time expenditure reduces discretionary time. A service provider can increase the value perceived by the customer by minimising the amount of time required to enjoy the service.

Time Cost

The time cost concept forms the foundation of a method to measure quality of service delivery. The worst level of service occurs in countries women walk for hours to obtain their family's daily amount of water. In developed reticulated water systems, the time investment by consumers is marginal and only becomes noticeable in the case of service failures or with inefficient facilitating services such as billing. The value perceived by customers can be maximised by minimising their perceived cost, minimising the amount of time they need to invest in enjoying a water service.

Psychological Cost

The psychological price encompasses the mental effort customers need to expense in purchasing or consuming the service. With water, the psychological cost is generally marginal, but as soon as the service fails, the psychological price increases dramatically, thereby decreasing the perceived value and leading to unhappy customers.

Another aspect is the sociological price, which relates to how the purchase impacts how other people view us. Sociological cost is relevant to water users in that, for example owning a lovely garden or swimming pool enhances the customer's prestige in their social network.

The type of price that I want to focus a bit more on is time. People need to spend their time to obtain water, and around the world, things are very different. The worst possible water service imaginable you would find, for example, in arid parts of Africa where women spend hours every day to get their daily ration of water.

There are some estimates that women around the world, you never see men carrying water, spend about 200 million hours every day to obtain water. In developed countries, customers use a negligible amount of time on obtaining water. Customers only get actively involved with the service when it s unavailable or unsafe. In worst cases, they might need to boil the water before they can use it.

The Value of Water and the Tap Water Value Proposition

Understanding how your customers assess the value of a service is the first step in developing a water value proposition enhances customer experience. The price of water, monetary, psychological, sociological and time, is so low that any disturbance in the value equation will lead to dissatisfaction. This thought leads to a previous proposition I made on this blog; the best possible water utility is invisible to the customer. An invisible water utility provides services that are so seamless that customers pay a negligible time price.

Deliberations about the value water seem at first instance to be a foregone conclusion. Water is of infinite value because we need water just like we need air and food to stay alive. This is, however, a simplistic view as we only need a relatively small amount to sustain life, anything beyond that is discretionary. In this article I will describe the complexities of the the value of water as a construct and propose an alternative perspective to define it. From this layered definition of value we can start defining the value proposition of water to improve customer engagement in tap water.

Tap Water Value Proposition

With this multi-layered concept of the value of water we can define a meaningful tap water value proposition—a promise to the customer regarding the value of the provided service. The value proposition is not merely a slogan or a branding exercise. A meaningful value proposition is communicated in everything a service provider writes says and more importantly, does—within the tap water context, customer service stretches from catchment to tap and to the water bill.

There are only two ways to maximise the value perceived by the customer: increase the perceived benefits or decrease the perceived cost. To maximise the perceived benefits of the service offering, water companies should focus their communication on the higher order needs water use satisfies. Many water utilities highlight the technological aspects of service provision, instead of the higher order benefits it provides.

The other side of the value equation involves lowering perceived cost. To lower the perceived cost of water services it is important to provide a high level of service in order to minimise the time price paid by customers. Water companies can focus on finding the root cause of customer communications and seeking to eradicate these causes so that there is no more need for consumers to contact the organisation. The perfect water utility is invisible to the customer.

Tap Water Advertising

Water utilities should use their value proposition to guide how they position themselves within the community. Water utility branding should closely follow the value proposition.

Marketing wisdom dictates that communication for services that are highly tangible, like water, should focus on the intangible aspects.

So instead of focusing on technology or emphasising on the physical qualities of the water, tell customers what intangible benefits they get from their tap water. Most discussions about water focus on its life-sustaining properties, but tap water is so much more. Using tap water is an essential part of modern life and maintains the lifestyle we have come accustomed to.

Having a shower is a perfect place for generating inspiring ideas; water is an essential ingredient in virtually every single recipe; water performs a crucial role in some of the most intimate moments in our lives.

The slide show below provides some examples on how the intangible value of water can be communicated, beyond the pipes, pumps and plants. These ads communicate the intangible dimensions of water and show that using water is not about the water itself, but about the value that water adds to our life. Advertising is not about convincing people with logical arguments but about communicating the value proposition that the utility provides beyond plants, pumps and pipes.

Water Utility marketing

If you like to find out more about using marketing theory to manage the experience of water utility customers, then please consider reading Customer Experience Management for Water Utilities by Peter Prevos.

Customer Experience Management for Water Utilities: Marketing Urban Water Supply

Practical framework for water utilities to become more focused on their customers following Service-Dominant Logic.

Share this content