The Psychology of the Recycled Water Yuck Factor

Peter Prevos |

2292 words | 11 minutes

Share this content

Using sewage to create drinking water, or recycled water is a controversial topic in many parts of the world, especially in places where drought has forced utilities to develop alternative sources of tap water. In 2006 the Australian city of Toowoomba faced an extreme water supply problem and held a referendum asking its citizens whether recycled water should be added to the potable supply. This referendum led to emotional outbursts, and the proposal was eventually rejected. Some commentators on this event referred to the so-called ‘recycled water yuck factor', which is an emotional reaction of repugnance towards certain foods and medicines. This article explores a psychological mechanism that causes this response and provides some suggestions on how to effectively promote the idea of using sewage to create drinking water.

The importance of origin

From a marketing point of view, using treated sewage to create drinking water is a proposition that 's hard to sell to customers. The origin of water is the most important aspect of the marketing of water, a concept masterfully used by bottled water companies. The importance of the (perceived) source of water was illustrated in a study which investigated whether there is a difference in willingness to pay depending on the name of water service.

The research found that customers had a higher willingness to pay for “recycled water” than for “treated wastewater”.1 Although the study indicates that there are differences in valuation based on the perceived origin of the water, no explanation was provided for this phenomenon.

The psychology of disgust and the recycled water Yuck Factor

There is no rational reason to oppose using sewage to create tap water. Regardless of technology, the natural water cycle ensures that all sewage will eventually become fresh water and most likely will find its way to somebody's tap. Human psychology is, however, more complicated than this simple rational line of thought.

Our deep-seated negative overall attitude towards faeces leads us to maintain a negative attitude towards anything that is related to it, including recycled water. Rationally speaking, this is a fallacy and known as the Wisdom of Repugnance, or the yuck factor. People arguing against recycled water use a non-rational ‘appeal to disgust'. They believe that a natural negative response to something should be interpreted as evidence for the intrinsically dangerous character of that thing. Although this is not considered a rational argument, it is nevertheless valid because we cannot ignore our innate psychological drives.

The psychological mechanism at work is the well-known principle of classical conditioning, also known as the Pavlov Reflex. Our cultural surroundings largely condition our tastes. Psychologists have researched these issues in detail. Faeces are a universal disgust substance that is deeply seated within our psychological make-up. This disgust is, however, not innate—we develop this feeling of disgust through conditioning.2

Yuck Factor Laboratory

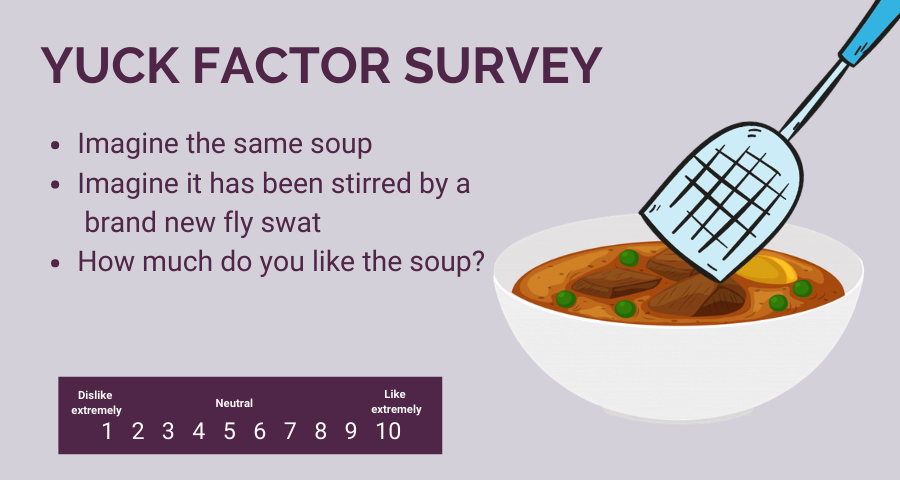

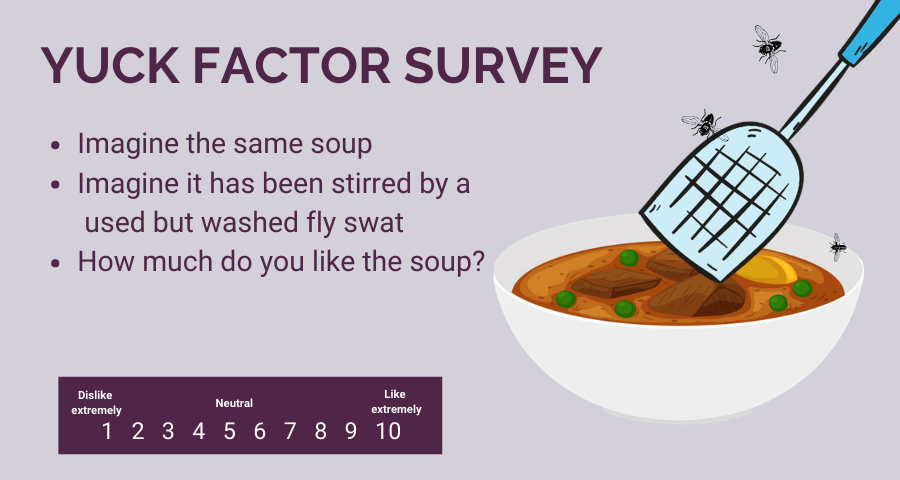

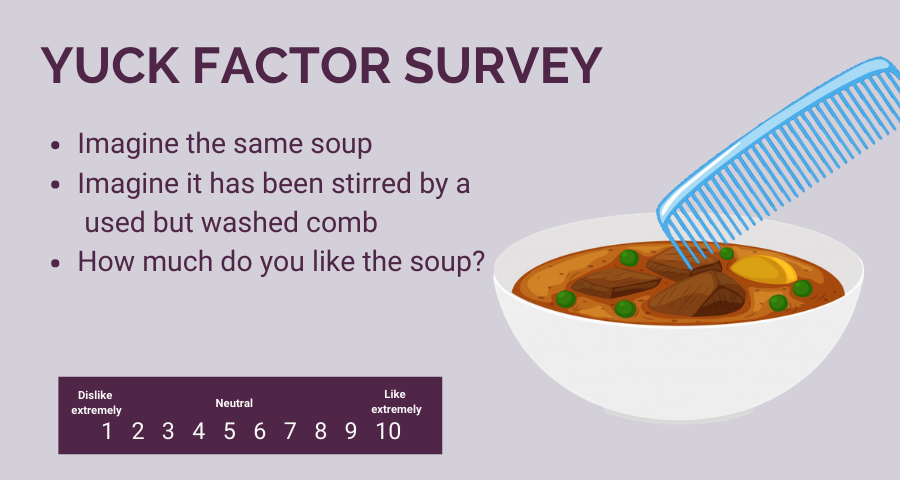

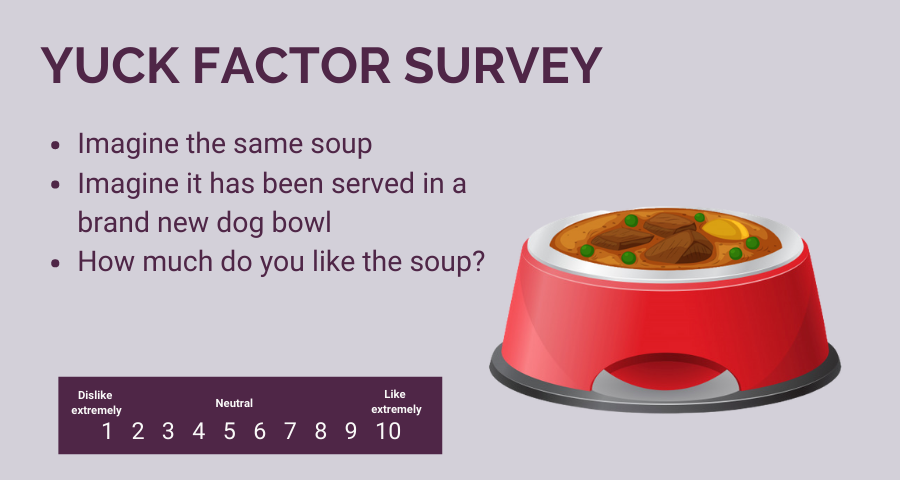

Psychologist Paul Rozin has undertaken several experiments to test aversion to a range of stimuli. The slides below show the questionnaire the researchers used in groundbreaking research in 1988. They asked people to rate how much they desire a certain item of food. In some cases, they combined the food with another stimulus, such as a cockroach and asked the same question.3 Flick through the slides by clicking on the arrow on the side. Answer each question on a scale from 1 to 9 of how much you like what is presented in the question.

What we see in this experiment is that the context in which the bowl is placed influences the attractiveness of the soup. None of the changes to the soup did, however, rationally modify the soup in any way. This experiment is based on the same principle behind the idea to use a special spoon to serve food to your pet—there is no rational reason to do so, but the perception of disgust is strong enough to motivate people to buy special spoons for their pets.

This experiment can be repeated using different water scenarios: straight from a spring, from a treatment plant, sourced from sewerage, downstream of a sewerage treatment plant and so on. This type of research should be conducted as it would assist utilities to sell better the proposition of using purified sewerage as drinking water.

Cultural Differences in Promoting Recycled Water

Direct Potable Reuse is a hot topic in areas where alternative sources of water are becoming scarce. There is a lot of fear in the industry because customers are not likely to accept this solution readily, due to our learnt attitude towards faecal matter, also known as the Yuck Factor.

Water utilities have tried a wide range of strategies to convince communities to encourage drinking recycled water. The general advice is to educate customers about the process. One of the rules of social marketing is, however, that rational appeals to change attitudes are not very useful. Clear examples of this practice are the many anti-smoking or anti-speeding ads that use emotional appeals to modify the viewer's attitude towards smoking or speeding.

Some commentators recommend using euphemisms for recycled sewerage such as 'impaired water' instead of polluted water. Some of these are weasel words and should not be used as people see through the ruse.

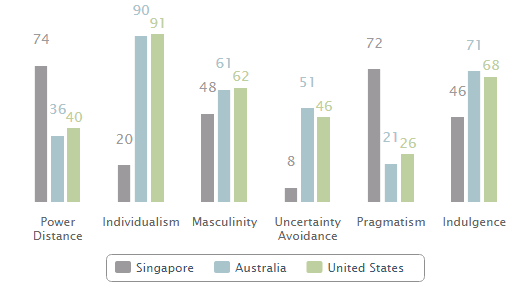

Singapore is one country which effectively implemented Direct Potable Reuse (DPR). However, comparisons with Singapore are not straightforward since due to cultural differences between this country and Anglo-Saxon countries. Salient differences in culture can be identified using the system defined by Geert Hofstede.

- Power Distance: the extent to which the less powerful members of institutions and organisations within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally.

- Individualism: the degree of interdependence a society maintains among its members

- Masculinity: the level of interdependence a society maintains among its members.

- Uncertainty Avoidance: The extent to which the members of a culture feel threatened by ambiguous or unknown situations and have created beliefs and institutions that try to avoid these.

- Pragmatism: the extent to which people attach more importance to the future, fostering pragmatic values towards rewards, including saving and capacity for adaptation.

- Indulgence: the extent to which people try to control their desires and impulses.

The data shows that the cultural profile of Australia and the USA are very similar. There are, however, notable differences between the cultures of Singapore and Australia/USA that need to be taken into consideration when comparing Direct Potable Reuse acceptance in these countries.

The Power Distance level for Singapore is almost double that in the other countries. Power distance influences the acceptance of government initiatives, such as DPR. The higher the level of Power Distance, the more likely a proposal is accepted.

The level of Individualism in Singapore is much lower than in Western countries in general. A small degree of individualism would make acceptance of initiatives such as DPR easier to implement because of the perceived public benefits. In Western countries, the high level of individualism complicates social marketing due to a large number of segments that need to be targeted to obtain coverage over a whole population.

The Masculinity dimension is almost the same in all three countries, which has thus no impact on differences in acceptance.

The low level of Uncertainty Avoidance predicts that people in Singapore feel much less threatened by the novelty of DPR than in countries with a high level.

The high degree of pragmatism in Singaporean society points towards a future-oriented view of water resources that includes thrift and a sense of saving for the future. This dimension is much less in Australia and the USA.

Finally, the Indulgence dimension is not very different between the countries

This comparison shows that firstly, understanding the value system of the consumers in the service area is essential to be able to craft an effective campaign for the acceptance of Direct Potable Reuse. Secondly, it shows that we cannot use an example used in one location and transpose that approach to another location.

Marketing Recycled Water

Although repugnance is a deep-seated psychological mechanism, the precise nature of the disgust mechanism is culturally determined. Just because a psychological mechanism is at work does not mean that it is hard-wired in our brain. Classically conditioned responses can be extinguished and reprogrammed. This change can, however, not be achieved by appealing to reason, as some industry experts proclaim.4

Marketing recycled water is a delicate art. The repugnance against faeces is too deeply seated to be extinguished by reason alone. The most effective advertising to change attitudes does not appeal to reason—don't try to convince your customers by telling them how great your treatment plants are. The best analogies to this problem are anti-smoking or safe driving campaigns. The most effective campaigns are those that appeal to non-rational aspects of smoking or speeding.

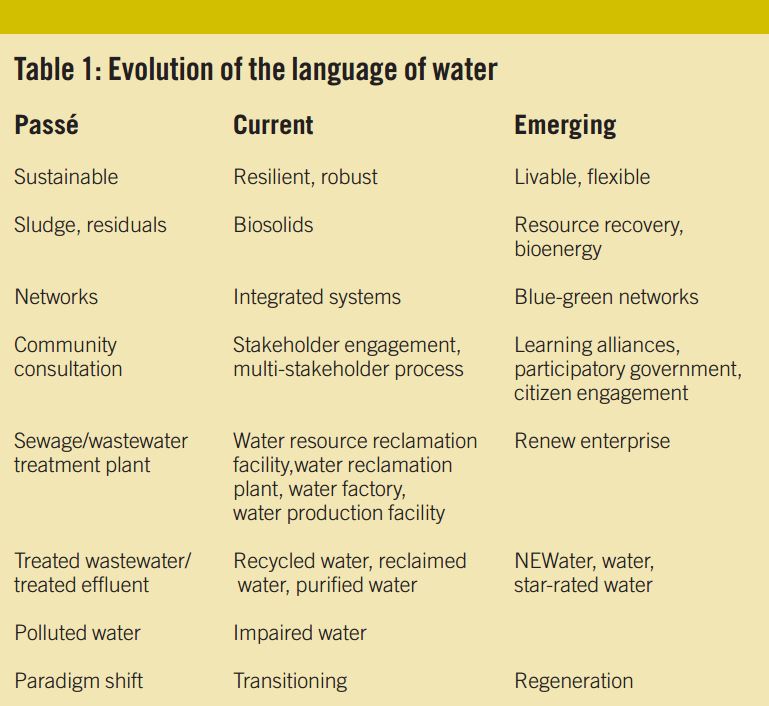

Sanitising public language

Weasel words are often used by demagogues, politicians and marketers to disguise what they are saying. A tax becomes a levy, we no longer live, we have a lifestyle and sacking people becomes downsizing. They are weasel words because they suck the meaning out of language, just like a weasel sucks eggs.5 Some weasel words, or buzzwords, are so common that they appear on special bingo cards.

This type of language is, unfortunately also familiar with water utilities. What used to be a sewage treatment plant is now a water reclamation facility, removing any reference to its origins. Sewerage Sludge is magically transformed to a 'biosolid', ensuring that the average person has no idea what its provenance is. These new terms suck all meaning from the original words.

In a recent article in Water21, the magazine for the International Water Association, John Baten proposed to take 'evolve' the language used by water professionals to even deeper levels of befuddlement, as evidenced by the table below.6

Some of these suggestions are even sucking the life out of the existing weasel words. To call a sewage treatment plant a 'renew enterprise' is confusing and deceptive. The regeneration—excuse me for using one of these terms—of treated effluent to Star-rated water is a total obfuscation of reality and removes water users even further away from the problems in our water supply chain.

Having said this, a careful choice of words is important. Empirical research demonstrated that framing 'treated wastewater' as 'recycled water' changed perceptions of the product by consumers and increased their willingness to use and to pay for the service.7

The removal of any reference to poo in the case of treated sewage circumvents the Yuck Factor—the psychological mechanism that prevents people from accepting treated sewage as drinking water. But this is nothing more than a cheap magic trick that will not be able to deceive water users into accepting what they know to be the truth. An example of direct communication about sewerage is the Twitter feed of Daniel Gerling, who is preparing a book on the cultural history of excrement. His language is clear and straightforward, and the impact of his word choice forces people to face the issue.

This type of language will be more harmful than helpful in our industry. Only by calling things by their proper name can we educate consumers about the water cycle and move forward in securing water for the future.

Given the intense disgust related to sewerage, telling people that they should drink and shower in recycled water will immediately activate the Pavlovian disgust reflex. The most effective way to sell the idea of using sewerage to create potable is to increase the level of trust customers have in the organisation, using origin strategies.

Don't emphasise the sewerage aspect of the water or the high-tech treatment facilities—emphasise the natural water cycle by using emotive images of pristine water flows. Focusing on the non-rational aspects of water consumption will increase customers' involvement with utilities and ultimately have a positive influence on their perceptions of quality and trust in the organisation.8

What do you think? How can we negate the Yuck Factor and make using recycled water as potable water acceptable?

Customer Experience Management for Water Utilities: Marketing Urban Water Supply

Practical framework for water utilities to become more focused on their customers following Service-Dominant Logic.

Menegaki, A. N., Mellon, R. C., Vrentzou, A., Koumakis, G., & Tsagarakis, K. P. (2009). What's in a name: Framing treated wastewater as recycled water increases willingness to use and willingness to pay. Journal of Economic Psychology, 30(3), 285–292. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2008.08.007.

Rozin, P., Haidt, J., & McCauley, C.R. (2008). Disgust in M. Lewis, J.M. Haviland-Jones & L.F. Barrett (eds.), Handbook of emotions, 3rd ed. (pp. 755–776). New York: Guilford Press.

Rozin, P., Fallon, A., & Mandell, R. (1984). Family resemblance in attitudes to foods. Developmental Psychology, 20(2), 309–314.

Russell, S., & Lux, C. (2009). Getting over yuck: moving from psychological to cultural and sociotechnical analyses of responses to water recycling. Water Policy, /11/(1), 21. doi:10.2166/wp.2009.007.

Don Watson, Watson's Dictionary of Weasel Words, Knopf, 2004

Baten III, J. (2014). One Water: Uniting around a new water language. Water 21, (February), 12–16.

Menegaki, A. N., Mellon, R. C., Vrentzou, A., Koumakis, G., & Tsagarakis, K. P. (2009). What's in a name: Framing treated wastewater as recycled water increases willingness to use and willingness to pay. Journal of Economic Psychology, /30/(3), 285–292. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2008.08.007.

Cohen (2000). Consumer involvement–driving up the cost. Consumer Policy Review, 10(4), 122–125; Espejel, Fandos & Flavián (2009). The influence of consumer involvement on quality signals perception: An empirical investigation in the food sector. British Food Journal, 111(11), 1212–1236.

Share this content