An Introduction to Human Resource Management in Hanoi

Peter Prevos & Ian Watson |

9033 words | 43 minutes

Share this content

A major attraction of travelling to other countries is that people are different to what we are used to at home. A few hours in an aeroplane carries us to places where an incomprehensible language is spoken, exotic food is eaten and almost everything else is different from what we are accustomed to. This is most certainly true for people travelling from Australia to Vietnam. The organised chaos of Hanoian traffic, the colourful markets and the narrow streets in the Old Quarter—everything is different. If everything is different, then it can be assumed that people also manage organisations in a different way and as such also manage people differently.

The economy of Vietnam is transitioning from a centrally planned to a free market system and has moved from a situation of crisis after the war against the Americans to a vibrant, fast-growing nation. The main question for this research is to provide a description of contemporary Human Resource Management in Hanoi, within the context of their transitioning economy.

This project is part of a research expedition to Hanoi, undertaken by the Graduate School of Management of La Trobe University, with assistance from Hanoi University. Data was gathered through site visits to seven local businesses and government organisations and through five confidential interviews with managers of local businesses.

Vietnam has gone through enormous changes since the introduction of Doi Moi, Vietnam's economic restoration policy that commenced in 1986, the government policy that seeks to transition the Vietnamese economy from a centrally-planned to a market-driven economy (Williams 1992). The process of transition in developing economies has a major impact on the way business is adopted (Warner et al. 2005) and the way Human Resource Management practices are conducted.

Several researchers have investigated management styles in Vietnamese organisations and found significant differences between Vietnamese and Western styles of management (Nguyen 2000; Quang and Vuong 2002; Rowley and Abdul-Rahman 2008). Country culture is, however, not a homogeneous phenomenon and significant differences between the work values of North and South Vietnamese management exist (Ralston et al. 1999). This report is thus focused on Human Resource Management in North Vietnam and specifically the capital Hanoi.

A literature review of Human Resource management in Vietnam shows that Vietnamese management styles in the state sector can be “bureaucratic, familial, conservative and authoritarian”, emphasising clear reporting relationships, formal communication and strict control (Quang and Vuong 2002: 52). The familial style was also widely accepted in Vietnamese enterprises; developed from family workshops. In contrast, Quang and Vuong (2002) further found that a participative management style was often practised in the joint venture sector, where expatriate managers brought in Western and Japanese principles of management. Rowley and Abdul-Rahman (2008) researched the existence of convergence towards a Western style of management in Vietnamese Human Resource Management practices. They found evidence of this occurring, but argued against the use of a universal Western-inspired model of Human Resource Management and described an alternative model based on Asian values.

Following the initial review of the literature, two research questions were formulated, both very open, to allow for flexibility during the research:

- What is the role of Human Resource Management in transitioning economies?

- What are Human Resource Management practices in contemporary Vietnam?

The purpose of the research was not to determine how Human Resource Management in Vietnam relate to business performance, but to examine what Human Resource Management practices are actually used. The qualitative research data is analysed in detail, combined with further literature review. From the analysis, three major topics emerge.

Firstly, Vietnamese managers have a salience for management theories origination outside of Vietnam, particularly Japan and the United States.

Secondly, companies seem to rely on social networks for recruitment. This is in contrast to most Australian organisations, where public advertisements are the dominant vehicle for recruitment. Research by Breaugh (1981: 145) showed that the source of recruitment is “strongly related to subsequent job performance, absenteeism and work attitudes” and that people recruited through newspaper advertisement missed almost twice as many days as those recruited through other sources, such as employee referrals.

The third finding is an indication that performance management in collective cultures, such as Vietnam, is more effective when aimed at improving the collective rather than focusing solely on the individual. Further detailed research is required to validate this hypothesis.

The managerial relevance of this research is to provide insight into Vietnamese Human Resource Management practices for those considering to invest or work in this country. The findings in this paper can also have implications for the way in which recruitment practices are conducted in Australia, specifically the use of social networks to find suitable candidates. The relevance of this report extends also into the academic realm as the secondary purpose of this project is to assess the usability of Grounded Theory in Human Resource Management research.

Literature Review

Human Resource Management in transitioning economies

With the introduction of Doi Moi in 1986, Vietnam has become a country with an outwardly paradoxical system, simultaneously maintaining a socialist system and a capitalist free market economy (Rowley and Abdul-Rahman 2008). This combination of socialism and capitalism seems paradoxical, but the duality of systems fits well within the Daoist inspired perspective of Vietnamese culture (Templet 1998).

A transitioning economy, such as is the case in Vietnam, is defined as one that changes from “plan to market” (Warner, Edwards, Polonsky and Pucko 2005: 3). With the collapse of the Iron Curtain in 1989, many European countries commenced the journey towards a free market economy. Before the dramatic events in Europe, countries in Asia independently started their transition.

China introduced reform after the death of Mao Zedong in 1976 and Vietnam introduced their economic restoration policy in 1986 (Warner et al. 2005). The term 'transition' is somewhat problematic as the end situation is not clearly defined. Given the unpredictability of complex processes such as macroeconomic change, the endpoint of transition cannot be known a priori (Warner et al. 2005). After the collapse of communism in Europe, Fukuyama (1992) euphorically proclaimed that this signified the final victory of the free market economy and that all countries would converge towards a unified economic system. Recent history has, however, falsified Fukuyama's predictions. The rise of Islamic banking as a viable and competitive alternative to conventional systems is a case in point (Khan and Bhatti 2008). The discussion about the nature of macroeconomic systems is complex and outside the scope of this report. Of particular interest to the Human Resource perspective is not so much the end goal, but the process of transition.

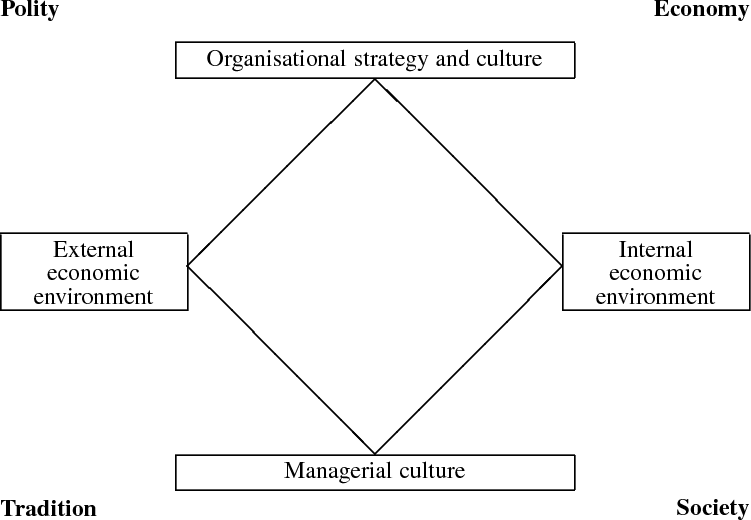

Warner et al. (2005) describe the process of transition from a centrally-planned to a free-market-economy in four dimensions (Figure 1). They describe a process that commences with changes in the External Economic Environment, usually the opening of foreign trade into the transitioning country. As the barriers to imports fall and more foreign products enter the market, competition in the internal market increases, which creates a link between the external and internal economic environment. In Vietnam, the start of the restoration process included a liberalisation of the import of consumer goods (Irvin 1995).

The second wave of reform is related to the Internal Economic Environment. Increased competition caused by foreign competitors entering the market leads to changes in prices as the balance of supply and demand alters. This process also involves a reform of the financial system of the transitioning country, which is an ongoing process in Vietnam (Dinh 1997; Ninh 2003; Thanh and Quang 2008). Changes in the economic system make capital more readily available and facilitate entrepreneurial activities. One major consequence of the liberalisation of the Vietnamese economy is that the number of State Owned Enterprises (SEO) has been reduced from 12,000 to 6,000 (Warner et al. 2005).

The process of divestment and privatisation of State Owned Enterprises is still underway and is managed by the State Capital Investment Corporation, who seek to divest a further 200 SEOs over the next two years (SCIC 2009). Changes in the external and internal economic environment initiate the third wave of reform, which is related to how organisations achieve their goals. Economic forces and changes in the competitive landscape cause organisations in transitioning economies to reassess their Organisational Strategy and Structure. This is the moment where businesses move from a reactive to a proactive approach in their response to the reforms. Changes in Organisational Strategy and Structure can, however, not be successful unless the Managerial Culture of an organisation evolves into a performance-based system (Warner et al. 2005).

The fourth aspect of the transitional model, Managerial Culture, involves changes in the way individual managers approach their work. The changing roles of managers in transitional economies can be linked to the often cited division of labour for managers described by Mintzberg (1971). In a planned economy, the role of managers is not as significant as in a free market model. For example, in a free market model managers are prime resource allocators, whereas in a planned economy resource allocation is controlled by politicians. This implies that the demands on managers in planned economies are lower than in a market economy. More importantly, the demands on managers in a transitioning economy, including their Human Resource Management skills, are even higher than in an established market economy (Warner et al. 2005).

The model described by Warner et al. (2005) provides a framework to analyse the processes of economic transition in countries where macroeconomic change is taking place. The framework seems to suggest a causality between the four aspects of transition in linear succession. However, each of the four aspects influences each other in a network of interdependence and reiteration of the cycle.

Changes in managerial culture improve the conditions for foreign companies to enter a country as local companies have obtained improved managerial competencies. Changes in organisational strategy and structure lead to changes in the internal economic environment because the institutions that govern the economic environment are also influenced by transitional processes. It could be argued that the process of transition is never ending, blurring the lines between a developed and developing economy in some instances. Human Resource Management plays an active role in the transitioning process as it can play a strategic role by enabling organisations to achieve their objectives (de Cieri et al. 2008; Hanson et al. 2008). In the background of the transition framework, Tradition, Society, Economy and Politics are local influences on this process of change (Warner et al. 2005).

Tradition and society are components of national culture and every management approach is deeply affected by local culture and values because management is, by its very nature, influenced by attitudes on how people are viewed in a culture (Hofstede 1996). In the next chapter, the nature of People Management (Human Resource Management) practices in Vietnam is discussed.

Human Resource Management in Hanoi

Human Resource Management is a wide and varied aspect of business management that can broadly be defined as “the policies, practices and systems that influence employee behaviour and performance” (de Cieri et al. 2008: 4). Human Resource Management practices are, in effect, a combination of applied psychology and sociology and, as such, a reflection of an organisation's view of humanity. They are a reflection of how people view themselves and the society in which they interact. As organisations are embedded in the society in which they operate, they will, therefore, reflect the culture of that country and the effectiveness of Human Resource Management practices will differ depending on the cultural landscape in which they are implemented.

Organisations in developed countries deploy a suite of practices, but it depends on the organisation's structure, goals, customer profile and societal context as to which practices are used. Given the plethora of approaches available to managers, the Western model of Human Resource Management can be considered inherently incoherent, which prompts one to question the notion of 'best practice' (Rowley and Abdul-Rahman 2008; Thang et al. 2007).

It would seem that there is a significant benefit to the HR function of a Vietnamese company becoming familiar with HR management methodologies used in developed nations. This would allow a Vietnamese company to quickly use and apply methodologies that have a good fit with the organisation's goals. However, there is the risk that a certain Human Resource Management practice currently used in Vietnamese companies, whatever those practices may be, has the potential to provide greater benefit to the company than the methodologies used in developed nations. Managers must be aware of sociocultural factors, particularly since the rational systems that originate from the developed economies tend to homogenise cultural distinctions (Hansen and Brooks 1994). The reinterpretation of HR management methodologies by Vietnamese companies may provide unexpected benefit beyond Vietnam. The introduction of total quality management into Japanese firms by W. Edwards Deming and its subsequent reinterpretation within the Japanese context has been not only a boon to Japanese firms, contributing significantly to their rapid development, but has also proven extremely beneficial and applicable to many Western firms (Gill and Wong 1998; Wren 2005). The benefits of documenting and understanding Vietnamese beneficial practices and also understanding modified practices is vital to the improving management, and in the case of this study, Human Resource Management in Vietnam, Asia, developing and developed nations alike.

When examining the Vietnamese context, it is difficult to determine whether there are intrinsically Vietnamese people-management practices without conducting in-depth comparative research. However, as suggested by Meyer (2006), there is a hazard of confirmation bias in the conduct of research when he suggested that: “Scholars working within existing theoretical frameworks may, in fact, limit their cognitive horizons … Empirical tests of hypotheses derived from mainstream theories may confirm the theory, even if the overall explanatory power is weak. On the surface, firm behaviour may be sufficiently similar to allow Western theories to be tested and confirmed, yet this does not imply that the same variables are actually important in the local context.”

The Flow of Human Resource Management Practices

Examining HR management practices in the Vietnamese context has been conducted in the past and has provided some useful information about the attitudes toward HR management in Vietnam. Management styles in the State-Controlled sector have been found to be “bureaucratic, familial, conservative and authoritarian”, emphasising clear reporting relationships, formal communication and strict control (Quang and Vuong 2002: 52). The heritage of family workshops is widely accepted to have given rise to the “familial” style of management that is commonplace in Vietnam.

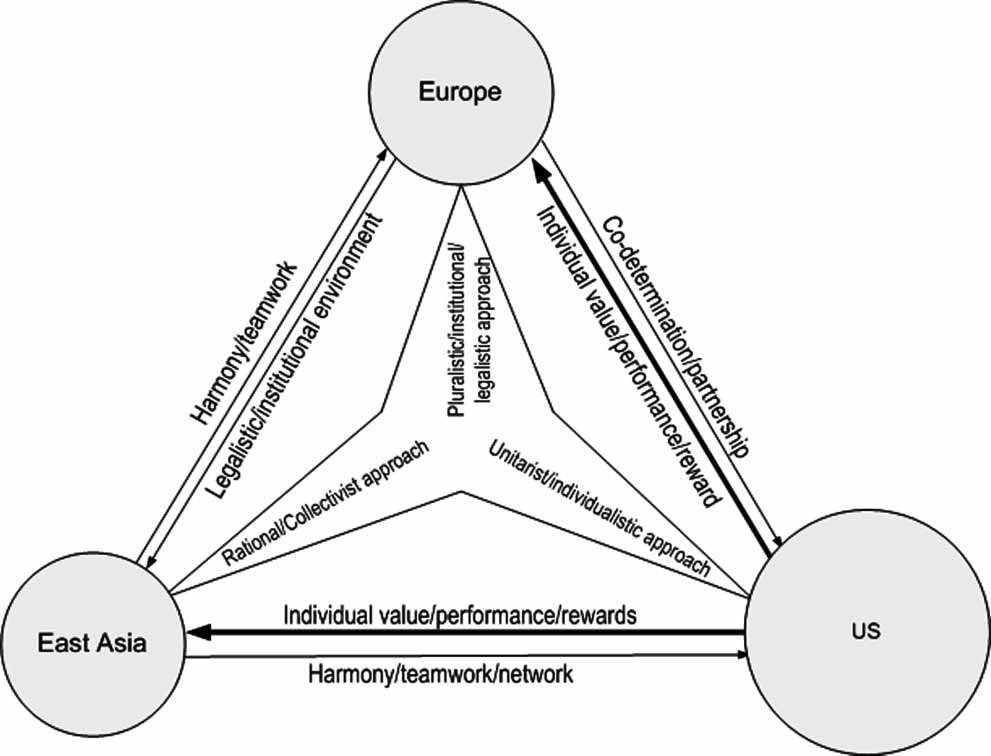

A participative work style is predominantly found in joint venture organisations (Quang and Vuong 2002) in which the Western style of management has been effectively imported to Vietnam via expatriate managers from Western Countries and Japan (Rowley and Abdul-Rahman 2008). While the work of Quang, Vuong, Rowley and Abdul-Rahman explain some aspects of Human Resource Management in Vietnam, there is a significant gap in scholarly research into Vietnamese Human Resource Management practice. In a broader sense, a model developed by Zhu (2008) seeks to explain how management practices flow between the United States, Europe and Asia (Figure 2). The development of Human Resource Management methodologies in East Asia is predominantly influenced by companies operating in those countries. As economies develop to a point at which Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is liberalised and subsequently increases, as shown in the model by Warner et al. (2005) (Figure 1), companies import their native Human Resource Management practices when moving to another country. In this respect, Human Resource Management practices are co-imported with foreign capital.

As foreign investment increases, there is also an increase in demand for skilled local labour. This skilled labour needs to be developed within a foreign or local education system. This is equally true for general organisational administration training, such as accounting and finance. Management training provided in Hanoi and in Western Universities appears to be mainly based upon Western management practices. As shown in the model below (Figure 2), the greatest flow of capital, human resources management practice and training is from the United States, where individual values and rewards are promoted (Zhu 2008).

With the strong inflow of foreign Human Resource Management practices as an economy develops, there is the risk that pre-existing practices may be lost. Through a more thorough exploration of existing Human Resource Management practices, two different but linked opportunities may be leveraged. The first opportunity is to promote and emphasise Vietnamese Human Resource Management to improve the success of companies operating in Vietnam. The second opportunity is the flow of beneficial Human Resource Management models from Vietnam to the rest of Asia and Western countries.

Vietnamese Human Resource Management Practices—Making the most of an opportunity

If there are pre-existing Human Resource Management practices that work particularly well within the Vietnamese context, there is an opportunity to thoroughly examine these practices and determine what works well within that context. With the opening of the Vietnamese economy to foreign investment there may be a limited window of opportunity to study and explore Vietnamese Human Resource Management, to define the endogenous practices and to document the success of these practices before they are, in effect, inundated by the Human Resource Management practices of the West and other more developed Asian nations such as Singapore and Japan.

There is a genuine and documented risk that education practices are in place that encourages, possibly inadvertently, the wholesale adoption of western Human Resource Management practices in emerging economies of Asia. Asian management scholars, notably from China, receive training in western Human Resource Management practices and are strongly encouraged to adopt these within their organisations. There is also encouragement for these scholars to publish in the top Western Human Resource Management journals (Tsui 2004).

The establishment of research and educational capacity in Vietnamese Human Resource Management training organisations, such as universities, would advance Asian management research. This would allow “scholars to shift their emphasis from theory application to developing new theories, and from benchmarking against Anglo-American models to comparative research within the region” (Meyer 2006: 120).

It is important to ensure that these Vietnamese practices are examined, defined, and incorporated into management training curricula. If there is a wider benefit of these management practices, then incorporation into Western models of Human Resource Management should be encouraged. As training in management theory, particularly with the rise and rise of foreign MBAs bring a greater emphasis on Western management theory, there is the risk that beneficial application of indigenous Human Resource Management may be lost to Vietnam and the rest of the world.

Wider benefit of Vietnamese Human Resource Management

The benefit of Vietnamese Human Resource Management practices being defined and applied in Vietnam is almost self-evident. It is more likely that the application of Vietnamese Human Resource Management practices will be successful and more beneficial because they have been developed within a single societal framework. However, there may be more benefit to understanding Vietnamese Human Resource Management practices. As can be seen in Figure 3, while the predominant flow of Human Resource Management practices is from the United States into Asia and Europe, there are also flows from Asia to Europe and the United States. Understanding Vietnamese Human Resource Management practices are likely to have the benefit of assisting Western countries to better manage their FDI efforts in Vietnam and there may be the additional benefit in promoting Vietnamese Human Resource Management practices in their associated organisations in the West.

The adoption of Western Human Resource Management practices in Vietnam may also have additional benefits outside of Vietnam. It is likely that scholars will apply their Western Human Resource Management training in their Vietnamese companies and will find that some practices will work and others will require modification to be successful. It is the modification of Western Human Resource Management practices in the Vietnamese context that may lead to improved management techniques that are applicable not only to Vietnam but also to Western Human Resource Management much as Deming's introduction of Western Management practices in Japan had significant benefit to the rest of the world.

The way forward

As described above, although some studies have been conducted (Budhwar 2009; Kamoche 2001; Nguyen 2002; Nguyen and Bryant 2004), there is a significant gap in the understanding of Human Resource Management practices that are currently being used in Vietnam. The transmission of Human Resource Management practices from the West does have benefit to Vietnamese organisations but also creates a risk that pre-existing Vietnamese Human Resource Management practices may be lost. It is through research that these practices may be defined, documented, and incorporated into HR training curricula in both Vietnam and the West. This will have a clear benefit for Vietnamese managers and, potentially, HR practitioners throughout the world.

This research project seeks to draw out Vietnamese management practices, to contribute to filling this gap in knowledge and help managers employ tools to assist with maximising the performance and well being of workers throughout Vietnam, Asia and the Western world.

Research Method

Formal interviews have been conducted in five privately-owned organisations, selected by Hanoi University, a research partner of the Graduate School of Management. Two of the interviewees were European managers working for Vietnamese companies. All respondents were university educated males between the age of 30 and 50. Only three interviews were dedicated to Human Resource Management as respondents were shared with other research groups in the Hanoi expedition.

The research was undertaken following the Straussian school of Grounded Theory (Jones and Noble 2007). All interviews were conducted very openly and covering a wide range of topics across the field of Human Resource Management and no hypothesis was defined prior to the data collection process. The questionnaire was loosely followed to allow for an open dialogue between the interviewers and the respondents. Depending on the reaction of the respondent, certain topics were discussed in more detail than was the case with other interviews. This method of interviewing allowed for greater flexibility and for gathering contextually rich information. It also provided an atmosphere in which participants were more open to providing data than in a closed interview.

All participants were fully informed about the purpose of the interview by means of a Participant Consent Form. This contained, besides the consent form, also a form to withdraw consent and an outline of the general purpose of the expedition. This form did, however, not contain a return address to submit the request and as such, no withdrawals have been received. One participant was willing to be interviewed but refused to sign the consent form. The interview continued, but the data has not been used in the report. All data obtained from the interviews remain confidential. Participating organisations and managers have been deidentified in this report. The raw research data is kept by the authors and will be destroyed after the results of the subject have been published by the University.

A collective application for all research groups in the Hanoi expedition was submitted to the University Human Ethics Committee (UHEC). The application excludes recording of the interview. No verbatim transcripts have thus been prepared and analysis relied solely on notes taken during the interview. Although some proponents of grounded theory argue against taping and transcribing of interviews (Charmaz 2006), it was found to be a restrictive requirement for this research. In one interview, the respondent was a German expatriate who only spoke Vietnamese and German. Since no Vietnamese translator was present, one of the researchers conducted the interview in German, simultaneously translating to the other researchers and taking notes. The directive not to record interviews restricted the research and constrained the quality of the data as the dynamics of the interview not always allowed accurate note-taking.

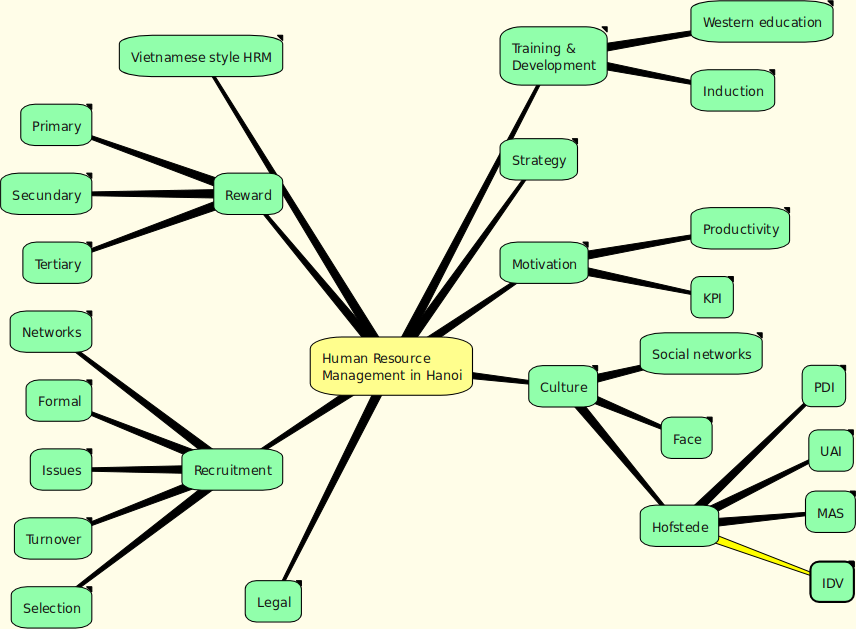

After each interview, the raw notes were transcribed by both researchers and in those cases where both were present, notes were compared to ensure consistency. The raw data were collated into a single document and coded in accordance with the standard procedures in Grounded Theory, as described in the previous chapter. After Coding, seven categories emerged from the data, some of which with their own subcategories. Sorting of all data revealed that some categories are linked to each other (such as Motivation and Reward).

A semantic diagram was used to prepare a memo for each category. Extensive memoing has been undertaken during the expedition itself and the analysis was substantially complete upon returning to Australia.

Based on this information, three categories were selected for further analysis, i.e. Vietnamese Style Human Resource Management, Recruitment and Motivation. Further literature review on the selected categories has been undertaken, enabling the formulation of three hypotheses. The limited amount of data did not allow drawing any firm conclusions about these phenomena. The last step in the research was the identification of a Core Category. It was found that the Core Category, binding all observed phenomena, is Collectivism. In order to stay as close as possible to the original words of the respondents, the raw data has been transcribed into four vignettes, which are provided in the next chapter, after which a detailed analysis of the data is provided.

Results

Company A

Mr A is the manager of a business department in a large distribution company based in Hanoi. The core competency of this organisation is the export and import of rice. In excellent English, Mr A explained that the business has recently horizontally expanded into the retail industry and currently operates some convenience stores and a supermarket in the city. They are committed to expanding their presence in retail but are on a steep learning curve.

They struggle with overseas competition because foreign companies have easier access to capital, better knowledge of the retail industry and better Human Resource Management systems. The main issue is that overseas companies have good training models and a “HR structure”. Company A is developing and implementing a suitable HRM approach with the assistance of consultants. They use Japanese and Western models as a reference, but select only those aspects they find suitable. Mr A smilingly said: “Western or Japanese model is not suitable”, but he did not provide details on how he determines which methods are more likely to be suitable.

Company B

Mr B is the manager of a large department store that focuses on home improvement, furniture and related products. He was expatriated from Germany a few months prior to the interview, which was conducted in German. He experiences difficulties in transforming the business because Vietnamese managers shy away from internal conflict and are always looking for harmony. Mr B is of the opinion that some internal conflict is required to make the business more successful. When asked his view on what it takes to be successful an European manager in Vietnam he resolutely answered: “adapt or die”.

He believes that the rate of social change in Vietnam is very fast and he anticipates social unrest because of this. Not in the form of riots or demonstrations, but through “passivität”, best translated as passive resistance against capitalist values.

He experiences trouble motivating local staff and showed statistics that the labour cost to turnover ratio in Vietnam is more than four times higher than in Germany. One of the reasons for this is that almost half of the store's employees are security staff. Shoplifting is a big problem and to deter people from stealing, photos of shoplifters that were caught are displayed at the store entrance. Mr B believes this works as a deterrent because it is a way to ensure that shoplifters literally lose face.

Individual productivity is, as shown by the above figures, very low in his business. Mr B believes this is a leftover of the transition from a Planned Economy, with high job security and no drivers to increase productivity. Being from former East Germany, he has seen a similar transition. However, he is of the opinion that the uptake of capitalist values by his staff is going slowly compared to his own experience. He said that the Vietnamese have an expectation of a job for life, without the requirement to be productive.

The business is introducing Key Performance Indicator (KPI) based salaries. He believes, however, that it is more important to reward subjective measures first because these are most lacking, i.e. keeping the store clean, correct merchandising and so on, rather than focusing on sales volumes. This relates back to the problems with staff motivation mentioned earlier.

Company C

Mr C is the Finance Manager of a privately owned distribution and logistics company that maintains trucks and warehouses, employing about 2,000 people.

When Company C recruits staff, they follow a three-step process. First, they review existing staff, then they use informal networks to find suitable people. Last option is to use a Headhunter, i.e. external recruitment agencies. The selection process depends on the vacancy they seek to fill. For middle and lower staff, the process involves psychological testing (IQ) and practical tests to ascertain whether they are suitable. For high-level positions, no testing is undertaken and Company C relies on references. Interviews with applicants are undertaken after the testing or obtaining references.

An important selection criterion for Company C is the applicant's perceived adaptability to their business culture. They target Vietnamese people that work at multinational corporations (MNC) because of their experience with working in an occidental management environment. However, these people find it hard to fit back into a Vietnamese business after working for an MNC.

The main difference between Company C and an internationally owned company is that in the latter, everything is very procedurised by using “SOP or something like that”, they follow “steps A, B and C”. In Company C there are no strict procedures to be followed and some people, particularly those that have worked for an MNC for a while, “get confused about what to do next”. They need staff who are able to work in this environment.

Company C wants to upgrade their HR systems to match that of MNCs that operate in Vietnam. They believe the best way to achieve this is to use a western HRM model, adapted to Vietnamese culture. Mr C reads Western management textbooks but chooses selectively on what to apply. They try to duplicate the systems used by MNC in Vietnam.

In Company C, lower and middle staff follow training on the job. They are developing the “soft skills” of middle management. There are no cultural issues with implementing western HRM models in the lower echelons because “lower people follow orders”. Vietnamese people are not fond of personal development beyond a certain point. There is currently no culture of “learning forever”. This is the old attitude and Mr C believes that a future recession will change that mindset.

Salaries are based on Key Performance Indicators, but they are different for each department. In sales, 20–30% of salary is dependent upon achievement sales volumes. Most staff members have individual KPIs. Secondary conditions such as annual leave, healthcare and share options exist for higher level positions. Tertiary conditions focus around staff outings, which is a Vietnamese tradition.

Company D

Company D is active in the hospitality industry and operates several pubs and restaurants in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, targeting Western expatriates and travellers. Mr D is the part owner and manager of the business. He is originally from the United Kingdom and moved to Hanoi several years ago. He speaks Vietnamese and is able to communicate with staff in their own language. Mr D has no formal management education and has a background in retail and pubs in England. This is where he has obtained a keen insight in the marketing of services.

One of the other owners of Company D also owns a charity in which street children are provided with an opportunity to be trained in hospitality. Through this connection, Company D is operated with a strong sense of social corporate responsibility. There is a strict separation between the charity and the business and they thus do not hire graduates from the charity. Company D recruits most of its staff from the groups of people that were not able to obtain a place in the charity training program but are considered suitable. The selection is followed by a conversation with Mr D, another manager and a Vietnamese staff member. The candidate has already been selected, so this is only an introduction to the business. Company D occasionally uses social networks to find new staff and expert jobs, such as accountants, are advertised. The success of their approach is illustrated by one girl who used to sell eggs in the street, became a cashier and is now studying to be an accountant.

The company focuses strongly on training and Mr D proudly mentioned that a former waitress, who is now the training manager of Company D, will soon move to Melbourne to undertake hospitality training at TAFE. Most new recruits are about 20 years old and have a basic knowledge of English because they used to shine shoes or sell lighters and so on. Because most new recruits are former street children, training of new staff members with the basics, including personal hygiene. All training is undertaken in-house through a mentoring system and for large groups by the training manager.

They just opened a new restaurant, which took six months to train all staff. New recruits have three months to learn the trade and start “busting tables and cleaning ashtrays”. Mr D is developing a staff handbook in Vietnamese and English. The handbook focuses on their rights and provides an overview of organisational values.

Company D provides a wide range of benefits, including help with accommodation, interest-free loans, vaccinations, English classes, a medical program (they even paid for heart surgery for one staff member) and a medical checks. They also provide a uniform and some new clothes for new staff, because they have no wardrobe of their own.

Some successful staff have been given a share in the company as a bonus. These are full shares which make them eligible to become a company director. They also provide free meals to staff when they are at work. Salary is performance-based, which is measured subjectively through conversation with their mentor. Some staff have doubled their salary in three months. Every two years they take their staff on an all expenses paid trip. They also provide transport to weddings and funerals.

It is a company rule that staff are not supposed to stand still and always look for an opportunity to provide customer service. Mr D said that Vietnamese jobs are usually quiet inactive and it takes some effort to ingrain this behaviour. Mr D also recounted an episode where he publicly escorted a staff member out of the premises because he was caught stealing. This caused problems for him because both the staff member and he lost face.

Analysis

From the data, seven categories emerged, some with their own subcategories:

- Vietnamese Style Human Resource Management

- Reward (Primary, Secondary and Tertiary)

- Recruitment (Social Networks and Formal)

- Legal

- Training & Development (Western Education and In-house provision)

- Motivation

- Culture (Face and Collectivism)

Analyses of the data showed that Reward and Motivation are closely related and that three categories, Vietnamese Style Human Resource Management, Recruitment and Rewards & Motivation, provided the best opportunities for theory building.

Vietnamese Human Resource Management

A recurring topic in all interviews was the existence and nature of a Vietnamese style of Human Resource Management. Most companies were in the process of researching Western and Japanese Human Resource Management methodologies and implementing these in their own organisations. There was a strong perception among the interviewed Vietnamese managers that the Western model of Human Resource Management is something to strive for. Although, methods were used selectively to ensure organisational and cultural fit.

Interviewees were not able to pinpoint the type of methodologies they believed to be suitable in a Vietnamese context and which were not. Vietnamese managers are embedded in their own culture and are not necessarily acutely self-aware of the differences between occidental and oriental culture. The fact that they have a personal preference for a certain management approach is an illustration of the culture in which they are embedded.

The need to research the suitability of existing management methodologies in emerging countries has been identified by several scholars (Budhwar 2009; Meyer 2006; Rowley and Abdul-Rahman 2008). Recent research by Thang et al. (2007) has shown that foreign practices which tend to be in harmony with the norms, beliefs and assumptions of Vietnamese culture have the best chance to improve business performance. Practices that are based on confrontation or impose ethnocentric methods are likely to fail. This was illustrated by Mr B, who lamented that Vietnamese managers in his organisation shy away from confrontation, something which he saw as necessary to create a healthy dialogue. This is consistent with the pluralistic approach preferred in Europe, as shown in Figure 5

Another aspect that was mentioned in several interviews and site visits was management training. Most managers expressed a preference for a Western-style management education. Larger companies send their people overseas to further their education. This aligns with the common Vietnamese tendency to prefer foreign products over locally made things. This attitude can be traced back to the time before Doi Moi, typified by a lack of quantity and quality of consumer goods (Thang et al. 2007: 125). The popularity of Western management education in Vietnam can also be seen as a result of the many development projects over the past decades, providing management education (Napier 2008).

From the observed salience for foreign Human Resource Management approaches a first hypothesis can be formulated.

H1 : Vietnamese managers have a preference for adopting Human Resource Management practices with a foreign origin.

This hypothesis may actually be proven incorrect in that the co-importation of capital and Human Resource Management practices outlined in Chapter 3 has led to Western Human Resource Management training being more widely available rather than being preferred. No firm conclusion can be drawn from the obtained data.

Reward & Motivation

Reward mechanisms can be categorised into three distinct types. Primary reward is the monetary remuneration an employee receives. Secondary reward refers to all non-financial entitlements, such as annual leave, lunch breaks and so on. Tertiary reward refers to the social benefits of being part of an organisation, but which are not part of the formal employment relationship. Primary reward mechanisms outlined in the site visits and interviews all follow methodologies very familiar to those used in Australian organisations, i.e. a focus on individual reward. All companies use a salary scale to value different jobs and maintain a bonus system to reward the performance of staff. A secondary reward was provided in all organisations in accordance with the Labour Laws of Vietnam (Chee and Dung 2008).

Most interesting was the emphasis of many organisations on tertiary rewards, such as staff outings, interest-free loans, transport to weddings and funerals, buying the occasional unexpected gift and also providing a “pleasant workspace” was mentioned. One company that excelled in this area was Company D. The businesses they manage are well known among travellers and expatriates in Hanoi and Ho Chi Min City because of the excellent service provided by staff. Staff seem to be much more motivated to provide great service than in other Vietnamese businesses. For example, in Company B, the manager expressed that staff were not self-motivated to provide service, which he attributed to Vietnamese culture. While Company D focuses on tertiary rewards and is achieving great results, Company B focuses on individual rewards and faces motivation problems. From these observations a second hypothesis can be formulated:

H2 : In collectivist cultures, tertiary rewards are more likely to motivate staff than primary and secondary rewards.

The hypothesis is theoretically supported through Vroom's Expectancy Theory (Robbins and Judge 2007) and empirical research that indicates that Vietnam and most other South-East Asian countries are collectivist in nature (Hofstede 1993).

According to Vroom, who follows a behaviourist model of psychology, the “strength of a tendency to act in a certain way depends on the strength of an expectation that the act will be followed by an outcome and on the attractiveness of that outcome” (Robbins and Judge 2007: 208). Vroom's model uses three concepts to explain motivation.

- Expectancy: the likelihood, as perceived by the individual, that exerting a given amount of effort will lead to performance.

- Instrumentality: the degree to which the individual is convinced that performing at a certain level will lead to desired rewards.

- Valance: the degree to which organisational rewards match an individual's personal goals.

The basic utility of Expectancy Theory is that, in order to enhance the performance of individuals, rewards need to be linked to the required behaviour and that these rewards are anticipated and wanted by employees. An employment relationship is underpinned by principles of mutuality and reciprocity (Heap 2008) in that employees expect a return for their efforts, as outlined in Expectancy Theory.

A return can be provided to employees on three levels, as outlined above. Following the principle of Valance in Vroom's theory, rewards in a society with a predominantly collective nature should reflect this. In other words, a focus on tertiary rewards and social benefits will theoretically lead to a better performance outcome.

The data obtained in this research does, however, not provide sufficient evidence to confirm or falsify this hypothesis and further researched is required to test its validity.

Recruitment & Selection

The third result emerging from the data is the preference for social networks in the recruitment of new staff, this contrasts with Australian firms where newspaper advertisements are the prevalent way to attract applicants to new positions (Wooden and Harding 1998). The third hypothesis is thus:

H3 : Recruitment in countries with a collective nature, such as Vietnam, is primarily conducted through social networks.

The purpose of recruitment is to communicate the existence of a vacancy to those segments of the job market that an organisation seeks to recruit from (de Cieriet al. 2008). The recruitment process is influenced by several factors, as illustrated in Figure 6.

It is the recruiter's task to increase the likelihood of a match between the applicant and vacancy characteristics, in other words, to achieve job fit'. Job fit is bidirectional as vacancy characteristics need to match applicant characteristics and vice versa. Only a bidirectional job fit ensures that the incumbent will be in the best possible position to contribute positively to the organisation. This is achieved by controlling the three influencing factors. Human resource policies affect the characteristics of the vacancy (job design). Recruitment sources determine which segment of the job market is targeted and thus influence applicant characteristics. The recruiters themselves also influence the job choice through their impact on both job design and applicant characteristics. Using social networks as a source of recruitment influences applicant characteristics because the criteria upon which the social network is defined determine who will be considered for the position.

Breaugh (1981: 145) showed that the source of recruitment is “strongly related to subsequent job performance, absenteeism and work attitudes”. People placed through universities and to a lesser extent those sourced through newspapers were “inferior in performance” to applicants who were sourced through advertisements in professional publications (Breaugh 1981: 145), which is a form of social network. People recruited through newspaper advertisement missed almost twice as many days as those recruited through other sources, such as employee referrals (Breaugh 1981). The field study was conducted in one particular research organisation in the USA.

A possible explanation of this phenomenon is the Individual Difference Hypothesis in which it is stated that recruitment sources differ in the types of the applicants they reach (education, class, self-image and so on), which results in different performance outcomes. Following this theory, people recruited through employee referrals may be more capable or have a better cultural fit than individuals recruited from public sources because current employees and other members of the social network screen potential applicants before they consider them for a position in the organisation as their own reputation is at stake (Breaugh and Starke 2000).

It should be noted that recruitment and selection are two distinctly different aspects of Human Resource Management. Although people are recruited because they are a member of a social network, this does not imply that they are necessarily selected because of this. All respondents acknowledged that an interview formed part of the selection process and in some instances, psychological and technical aptitude tests were used to determine the most suitable candidate.

Core Category

Following the analysis of the identified categories, a core category emerged. The core category, i.e. the concept that ties the findings together, is the collective nature of Vietnamese society. This concept has been widely discussed in management literature, spearheaded by the research undertaken by Dutch sociologist Geert Hofstede (1983).

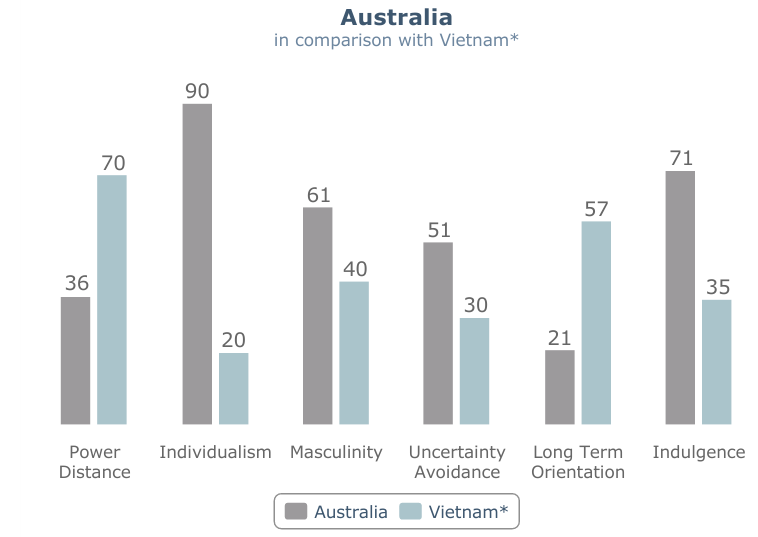

Collectivism emphasises human interdependence and the importance of a group. On the other end of the spectrum, individualism is the degree to which people give primacy to the individual over the group to which they belong. Countries with a high level of individualism (IDV, see Figure 7), such as Australia, prioritise individual rights over the rights of the collective. In countries with low scores in IDV, the collectivist societies, such as Vietnam, the rights of the individual are often subordinated to the collective (Hofstede 1983, 1993). The preference for using social networks as a means of recruiting staff is an expression of the collective nature of Vietnamese culture. Although this research was conducted with limited data, the preference for social network recruiting was also confirmed in many informal conversations with Vietnamese managers not partaking in the interviews.

The use of social networks is contrasted with the preference of newspaper advertisements in Australian firms, as identified by Wooden and Harding (1998). This is in line with the core category as Australia is considered an individualistic country (Figure 7.3) and newspaper advertisements focus on random individuals. Collectivism was apparent in how businesses manage staff performance. There seems to be a focus on tertiary rewards, which are also an expression of the collectivist nature of Vietnam. With regards to Primary and Secondary rewards, Thang et al. (2007) investigated the transferability of occidental management practices into Vietnam and found that individualism is one of the underlying assumptions for a pay-for-performance system. The long-held Confucian collectivist values in Vietnamese society will, however, make it difficult for these methods to be successful. A pay for performance system is more likely to be applicable to the younger generations. As the per capita, Gross Domestic Product of Vietnam rises, the level of individualism is also expected to rise, as shown by Hofstede (1993).

Conclusions

They say you come to Vietnam and you understand a lot in a few minutes. But the rest has got to be lived.

Graham Greene (1977), The Quiet American.

The research in Vietnam and associated literature review has unearthed some interesting prospects for further research into Human Resource Management in this country.

Firstly, even only a very limited amount of interviews were conducted, the contextually rich nature of the data and using the Grounded Theory approach allowed for the formulation of some promising hypotheses. It is, however, because of the limited number of observations that were able to be made that the results can only be considered hypotheses at this time. Grounded Theory is thus a potentially successful method for researching Human Resource Management practices in Vietnam. Given that many scholars recommend in-depth research in this region an opportunity is created to enhance the findings of this report through follow-up studies.

The first hypothesis states that Vietnamese managers have a preference for adopting Human Resource Management practices with a foreign origin. This preference may be because of a perceived superiority of foreign models or simply because Vietnamese practices are not very well documented. This illustrates the importance of foundational research into the actual methods used in Vietnamese organisations in order to be able to enhance the global body of knowledge in this area.

The second hypotheses, which states that in collectivist cultures, tertiary rewards are more likely to motivate staff than primary and secondary rewards, is based on only two observations but is supported by Vroom's expectancy theory and Hofstede's work on national cultures. Should this assertion be proven to be correct after subsequent research, it may have a significant impact on how both Vietnamese and foreign companies structure their reward portfolio.

Lastly, the finding that recruitment in the researched organisations is primarily conducted through social networks, combined with earlier research on correlations between recruitment source and staff performance, warrants further research. Australian organisations cast wide nets in their search for new staff members by advertising in newspapers distributed to anyone with an interest in local matters. If this hypothesis is confirmed, a model can be developed to manage social network recruiting, which could possibly lead to lower recruitment cost. This would be a recognition of Vietnamese Human Resource Management and alleviate the need to introduce models from the USA, which have shown to be not always successful.

References

Breaugh, James A. (1981) Relationship between recruiting sources and employee performance, absenteeism, and work attitudes. Academy of Management Journal 24(1): 142–147.

Breaugh, James A. and Starke, Mary (2000) Research on employee recruitment: So many studies, so many remaining questions. Journal of Management 26: 405–434.

Budhwar, Pawan (2009) Future research on human resource management systems in Asia. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 26(2): 197–218.

Charmaz, Kathy (2006) Constructing Grounded Theory. Sage Publications.

Chee, Patrick and Dung, Le Thi Tuyet (2008) Overview of the Labour Law in Vietnam. Asialaw June/July.

de Cieri, Helen, Kramar, Robon, Noe, Raymond A., Hollenbeck, John R., Gerhart, Barry and Wright, Patrick M. (2008) Human Resource Management in Australia. 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill Irwin.

Dinh, Viet D. (1997) Financial reform and economic development in Vietnam. Law and Policy in International Business 28(3): 857–892.

Egan, T. M. (2002) Grounded Theory Research and Theory Building. Advances in Developing Human Resources 4(3): 277–295.

Essential Services Commission (2009) Inquiry into an access regime for water and sewerage infrastructure services—Issues Paper. Available at: www.esc.vic.gov.au. Accessed 22 February 2009.

Fukuyama, Francis (1992) The end of history and the last man. Free Press.

Gill, R. and Wong, A. (1998) The cross-cultural transfer of management practices: The case of Japanese human resource management practices in Singapore. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 9(1): 116–135.

Hansen, Carol D. and Brooks, Ann K. (1994) A review of cross-cultural research on human resource development. Human Resource Development Quarterly 5(1): 55–74.

Hanson, Dalles, Dowling, Peter J., Hitt, Michael A., Ireland, R. Duane and Hoskisson, Robert E. (2008) Strategic management. Competitiveness & globalisation. Cengage Learning.

Heap, Lisa (2008) The Australian Charter of Employment Rights: Setting the standard for new legislation and good practice. Journal of Industrial Relations 40(2): 349–353.

Hofstede, Geert (1983) National Cultures in Four Dimensions: A research-based Theory of Cultural Differences among Nations. International Studies of Management and Organizations XIII(1): 46–74.

Hofstede, Geert (1993) Allemaal Andersdenkenden (Cultures and Organisations: Software of the Mind). Amsterdam: Contact.

Hofstede, Geert (1996) An American in Paris: The Influence of Nationality on Organization Theories. Organization Studies 17(3): 525–537.

Irvin, George (1995) Vietnam: Assessing the achievements of Doi Moi. The Journal of Development Studies 31(5): 725.

Jones, Robert and Noble, Gary (2007) Grounded theory and management research: a lack of integrity? Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management 2(2): 84–103.

Kamoche, Ken (2001) Human Resources in Vietnam: The Global Challenge. Thunderbird International Business Review 43(5): 625–650.

Khan, M. Mansoor and Bhatti, M. Ishaq (2008) Islamic banking and finance: on its way to globalization. Managerial Finance 34(10): 708–725.

Kim, Joo Yup and Nam, Sang Hoon (1998) The concept and dynamics of face: Implications for organizational behavior in Asia. Organization Science 9(4): 522–534.

Learmonth, Mark (2006) Doing critical management research interviews after reading Derrida. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management 1(2): 83–97.

Liamputtong, Pranee and Ezzy, Douglas (2005) Qualitative research methods. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press.

Meyer, Klaus E. (2006) Asian management research needs more self-confidence. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 23(2): 119–137.

Mintzberg, Henry (1971) Managerial Work: Analysis from Observation. Management Science 18(2): B97–B110.

Napier, N.K. (2008) Management Education in Emerging Economies: The Impossible Dream? Journal of Management Education 32(6): 792–819.

Nguyen, Nguyen, Foulks, Edward F. and Carlin, Kathleen (1991) Proverbs as psychological interpretations among Vietnamese. Asian Folklore Studies 50: 311–318.

Nguyen, Laam Huu (2002) Role and copetence profiles Human Resource Development practitioners in Vietnam. Ph.D. thesis, Texas A&M University.

Nguyen, Thang V. and Bryant, Scott E. (2004) A Study of the Formality of Human Resource Management Practices in Small and Medium-Size Enterprises in Vietnam. International Small Business Journal 22(6): 595–618.

Nguyen, Thang Van (2000) Work attitudes in Vietnam. Acadamy of Management Review 14(4): 142–146.

Ninh, Le Khuong (2003) Investment of rice mills in Vietnam: The role for financial market imperfections and uncertainty. University of Groningen. Available at: irs.ub.rug.nl/pnn/25039801X. Accessed 6 March 2009.

Quang, T. and Vuong, N. T. (2002) Management Styles and Organisational Effectiveness in Vietnam. Research and Practice in Human Resource Management 10(2): 36–55. Available at: rphrm.curtin.edu.au/2002/issue2/vietnam.html, downloaded 27 December 2008.

Ralston, David A., Thang, Nguyen Van and Napier, Nancy K. (1999) A comparative study of work values of North and South Vietnamese managers. Journal of International Business Studies 30(4): 655-672.

Robbins, Stephen P. and Judge, Timothy A. (2007) Organizational Behavior. 12th ed. New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Rowley, Chris and Abdul-Rahman, Saaidah, eds. (2008) The changing face of management in South East Asia. London & New York: Routledge.

SCIC (2009) State Capital Investment Corporation. Information brochure.

Storberg-Walker, Julia (2007) Understanding the conceptual development phase of applied theory-building research: A grounded approach. Human Resource Development Quarterly 18(1): 63–90.

Strauss, Anselm and Corbin, Juliet (1990) Basics of qualitative research. Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park: Sage.

Templet, Robert (1998) Shadows in the wind. Abacus.

Share this content